Knife Author Tim Hayward Pens An Ode To French Knives

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Just because the knife is a simple instrument doesn't mean it's a simple institution. Learn about the shape, construction and purpose of some of the world's most famous culinary tools with award-winning food writer Tim Hayward. His charts and essays reflect an enormous amount of knowledge we can't wait to sharpen our minds with. Think you know all the knives in a French cook's roll? Get ready to be inspired to sharpen your tools and chop, slice, dice and chiffonade your way to culinary glory. Reprinted with permission with permission from Knife

In a roll, a toolbox, on a rack or stuffed in a drawer, your set of knives is more than the sum of its parts. They might have been inherited or quietly nicked from other cooks, complicated and expensive purchases may have been made, but however you come by your knives, your kit is in an active process of evolution. A useless knife is got rid of, a damaged one either rejected or coaxed back into productive life. You might sharpen them obsessively or feel a constant, nagging, low-grade guilt that you 'really ought to get round to' a spot of maintenance. As your skills develop, you'll outgrow old favorites, aspire to new ones and eventually acquire them. No wonder people get obsessed about their roll... it's a chillingly accurate snapshot of their character.

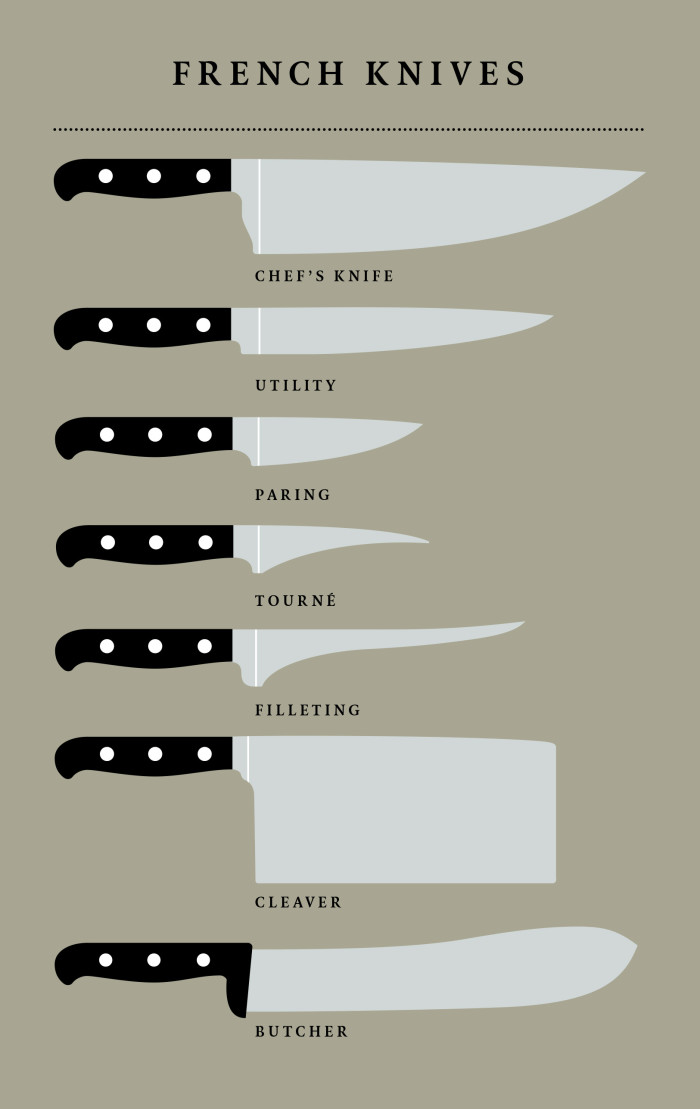

There always seems to be a master knife in the kit, the one that's in your hand the most. The classic chef 's knife, based on the time-honored French pattern, is the master knife in our culinary tradition. This makes sense because most high-quality Western cooking — at least as far as it's formally trained — is based on French. A modern chef could pick up Escoffier's knife and use it easily, and he would, had he got his hands on one, have been very comfortable with the contemporary version.

The curved blade rocks to mince meat and herbs, the length enables slices to be cut from big slabs of protein, the handle sits high so knuckles clear the cutting board. Chefs pride themselves on being able to do almost anything they need in the kitchen with just the one knife. It's perhaps unsurprising that buying a chef's knife is the first thing one does on self-defining as a serious cook. Sure, your mum had knives, you probably used one or two in grubby kitchens as a student, but the day you go out and intentionally drop $60 or more on a knife is the day you declare to the world that you're not just someone who makes dinner, you're now a cook.

Elizabeth David is often credited with relaunching serious cooking in the UK after the war and she saw the knife as key to taking cooking seriously. Though stainless-steel kitchen knives were available, she preferred the French provincial favorite, carbon steel — softer and easier to sharpen. Many older cooks still have a soft spot for the Davidian Sabatier with which they discovered garlic, olives and lemons — conveniently forgetting that the blade rusted like a bugger and turned the lemons black — and very few have survived the intervening sixty years of enthusiastic sharpening.

Today, the professional chef 's knife is more likely to have been made in Germany than in France, with Wüsthof and Henckels the two main competitors in the field. They are so beautifully, so scientifically manufactured that notions of individual 'craftsmanship' seem strangely distant. Their efficiency is total, their finish so flawless that it seems impossible to imagine that a human was involved in their creation and that is, in a strange way, reassuring. Like some gleaming component of an aircraft I'm flying in, I kind of don't want to believe that these knives were beaten into shape by a bloke with a hammer.

The secondary knives in the rack are the ones that do things the big knife can't. Boning and filleting require thinner, more flexible blades and often there will be a knife designed for an altogether different type of cutting — the kind of 'toward-the-thumb' whittling that works so well on vegetables. There's no way the 8-inch knife can be wielded that way: the deep throat that enables the knuckles to clear the chopping board puts the cutting edge in quite the wrong place. The standard roll for a culinary student today will probably include the chef's knife, a boner, a flexible filleter, a paring knife and a turning knife.

Beyond this, most cooks accumulate 'special' knives. Weird one-off specials that do one thing too well to ignore. Old-school classically trained pros will have a couple of melon ballers. These spoon-shaped cutters were routinely stolen from the pastry chef because they were so fast at coring tomatoes and cucumbers. I know one chef who keeps her grandfather's pocket knife just for removing the eyes from potatoes. I'm a great fan of the deviled kidney so I keep a small pair of locking forceps and a 10a scalpel for efficiently whipping out the fibrous cores.

The last thing in the kit will be an old favorite. A knife that's lived its life too well and too long and should really, by rights, have been retired years ago. But it's hard... really hard... to say goodbye to a tool you've loved and used. A tool you've adapted to use, whose shape you've formed. One that's given blameless and brilliant service.

There will always be that single old stager because, though all tools are about efficiency, function and fitness for purpose, knives have an extra emotional dimension. It's the part that demands that we care for our knives and it's the part that gives us a kind of 'pride in the roll.'