She Wrote The Book On Natural Wine

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

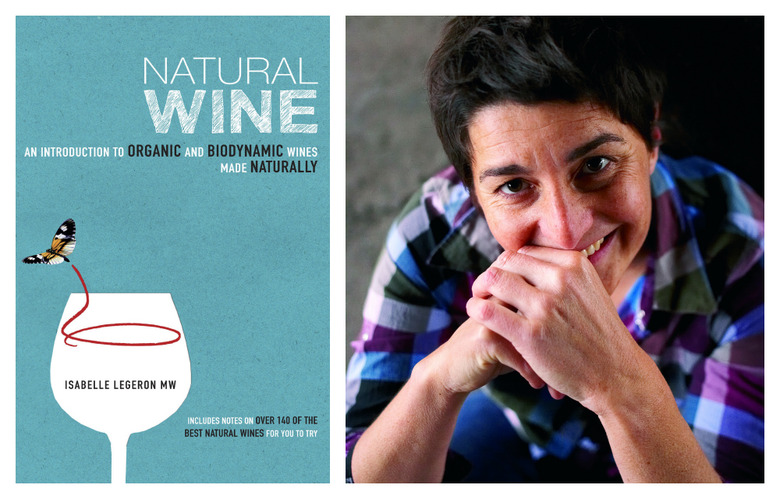

Recently, I had the pleasure of sitting down at Lafayette in New York with Master of Wine Isabelle Legeron, whose beautiful book, Natural Wine: An Introduction to Organic and Biodynamic Wines Made Naturally, was recently released in the U.S. In addition to running the programs of a couple of Michelin-starred restaurants in the U.K., she is working on developing an all-natural wine list for Belle Mont Farm, a fully sustainable new resort on the Caribbean island of St. Kitts. Here, she goes deep on the subject of natural wine, which we discussed, of course, while drinking craft beer.

First off, congratulations on Natural Wine! It's amazing. How long have you been working on it? Your whole career, probably?

Yes, but really, probably about a year. There was a lot of primary research because not a lot exists on natural wine, so you have to talk to a lot of people.

I was at a tasting today and the words "organic," "sustainable,"and "biodynamic" were all being thrown around without any qualification. How would you define "natural" wine, and how do you think people can be sure if a wine is natural or not?

Very simply, natural wine is nothing added and nothing taken away, and it's organic. Organic is the first level in terms of the foundation of natural wine. Then nothing has been added, so no sulfites, no yeast, no enzymes, nothing. It's not being refined or filtered. Obviously it's a bit more of a complex issue, because that only represents 20 or 30 growers in the world.

That's my next question. For example, using SO2 [sulfur] in the cellar. Let's say one dose of sulfur before bottling, which is something natural winemakers ostensibly do...

That's a very valid question. For me, the sulfite question is really up until the bottling stage. If you are to add sulfites, the bottling stage is probably the least damaging, because by that stage, everything has gone through its flavor profile, so you have the whole story. But that's nature: Some vintages are more difficult or volatile, then you need to intervene more or less.

And so you expect to see a proliferation of growers who are doing that? Because you said 20 or 30 – maybe there's 30 more in five years. But that's still not very many. Do you think it's more like in five years there's 200 more growers?

I think it's growing. I said 20 to 30, but there's close to a hundred if you look everywhere in the world. Yes, we're getting more and more people, for sure. In reality, even somebody who adds 10 or 20 parts [per million of SO2] at bottling, I still regard as a natural producer. If it were up to me to really define it, which needs to happen, it would have to be nothing added, nothing taken away.

You said "we," and I love that because "we" refers to this amorphous community of natural wine people. Do you think you need some sort of official body or legal framework?

I think it needs some organization, for sure. When I was researching this book, talking to growers, they feel that everyone is using the word "natural," whether it's organic or non-organic. I think a lot of people actually — all over the world — are beginning to use the word, so I think it needs to be protected so it has a little more meaning. There has to be some action taken, for example, by the EU.

The European Commission is looking at this stuff?

A little from the French side, but not a concerted effort.

Do you think that natural wine has to cost more to the consumer? Do you think consumers are willing to pay more for natural wine?

I think they are, but I don't think that it necessarily has to cost more to move from organic to natural. The question is: Do we actually pay for the real value of what we drink? In the U.K. market at the moment, people are expected to pay £5 for a bottle of wine, and then there's £2 duty, shipping — the rest is huge. But that's how people think the wines should be priced. Natural wine is not for everybody, and I don't think everybody cares. My agenda is not "Everybody needs to be drinking natural wine!" My issue is that there is no transparency, and what I wanted to do with the book is just lay out some arguments and some ideas, not necessarily come up with all the answers. For example, if you go to somebody at a bar and say, "They used fish derivatives to produce that bottle of Champagne," people might think that actually they don't want to be drinking that because they're vegetarians.

Or they use egg whites for fining[1].

Yeah. Or "I'm vegan, I can't have it." When people realize how wine is made, once they're in a position of choosing to believe in this artisanal product, once they have the story, they're prepared to pay for it. That's the thing with natural wine.

If it's not for everyone, how would you characterize the people that it's for?

I organize a fair called Raw, and when I look at the demographics and who's coming to the fair, what we're looking at is essentially people in their 30s and older. They're people who are into food, but they're also interested in alternative arts. They're people who ask questions, and maybe they choose what they do and how they do it. Then you've got more classic people who are maybe in their 50s and and older, who have invested a lot in wine and now they're looking for the next thing. They're starting to ask questions. They're interested in and read about what they drink and eat; they love flavors. I would say that's the typical crowd.

How do you help guests who don't see the names, styles or appellations they're familiar with on a wine list?

It's all down to the team. These wines need to be hand-sold. It's key to have the people in place that can tell the story. You're right, you can't pick up a wine list and say, "Oh, I see Sancerre and Pouilly-Fumé." At Hibiscus, where we used to have quite a conservative clientele, my wine list was completely conventional, and from one day to the next, we just got rid of everything and turned it pretty much completely natural.

Obviously you can spend days talking about how to train the staff, but how do you approach training people about natural wine?

I think the grower's story is really important. For me, natural wine is all about the human element. There are really people who plow with horses. The story is always super-heavy on the people behind the wine, then I try to free the staff from what they think wine should be. I think that in the wine industry, there's this vision that a Riesling should be exactly like this and if it's not, then, "Oh my God, this is not a Riesling." Wine has many facets; this is one aspect that we choose to work with.

I think one of the reasons natural wine hasn't caught on in New York is because people associate it with certain styles, like orange wine, or with techniques that are unusual on top of being natural. Do you have favorite examples of wines that are natural but still apply to some sort of conventional expectations?

I think that's easier with a red wine. But if you have the Henri Milans of this world, what they do in white and red, whether or not you knew what natural wine was, you would like to drink it. And Le Puy — for me this is a really classic textbook Merlot/Cabernet Sauvignon, but very old-fashioned. No extraction, no oak. Just a really gentle wine that can live for 80 years. So I think there are a lot of examples where people would not think it's actually a natural wine.

What were you surprised by in your book research? What did you not expect to find that you found?

I did a lot of research on the history of the use of sulfites. And you know what people always say in the wine industry about sulfites, justifying the use of sulfites, saying it's been used since the Romans...

Yeah, they burnt sulfur to clean the barrels or something.

But it's not true. I interviewed Patrick McGovern and a number of other historians and archaeologists, and there was no mention of the use of sulfur until the Middle Ages. They used sulfur, the Romans, but to clean houses. In the Middle Ages, it arrived for sanitizing barrels or whatever, but it wasn't an additive to wine until the late 19th century. It's a very recent thing.

There's a lot of mythology in wine education. It's funny. So anything else?

This beer[2], for example, for me that's a live product. I think the leitmotif of the book is really about the aliveness. Natural wine is about preserving life: the life in the vineyard, the life throughout the winemaking process. For me, in a way, what was really cemented through my research and writing the book was that actually this book is about life.

Contributor Chad Walsh writes about wine and other beverages. He is also the beverage manager for The Dutch in NYC.

[1] I once attended a tasting of experimental lots held by Château Margaux, home of the famed first-growth Bordeaux. Each year the estate conducts dozens of microfermentations. The barrels that were fined (a process by which the ions inherent in egg whites attract particulates from the wine) by four eggs beside those fined with six were so different that the room of overqualified tasters nearly erupted in a brawl.

[2] We were drinking Other Half IPA from Brooklyn.