The Big Freezy: How New Orleans Came To Run On Icy, Boozy, Bottomless Daiquiris

The Sazerac can claim a more elite status, carrying the legal title of New Orleans' official cocktail. But, the frozen daiquiri is far more ubiquitious around town.

"There's virtually nowhere you can go in the city and not see a daiquiri bar, or a restaurant that serves daiquiris," says Paris White, beverage manager at Pelican Bay, one of the newest additions to the city's snowballing frozen-drink industry. "We're a very festival-centered community," White says. "To me, the daiquiri just goes along with that type of culture and lifestyle. It's something that you can grab, and walk around with it."

By "daiquiri" — of course — we're not talking strictly about the classic recipe, incorporating rum, citrus and sugar and dates back to 18th century Cuba. The name, as its used in contemporary New Orleans society, is more of an umbrella term, covering any sort of frosty blend of booze and various fruity flavors. Heavy emphasis on the booze: 190-proof liquor is a common ingredient in these parts.

Exactly how the name got bent out of shape is unclear. But, Michael Mizell-Nelson, associate professor of history at the University of New Orleans, has a theory. "I think the popularity of the daiquiri during the disco era had a lot to do with the term bring selected," he tells Food Republic. Sweet, colorful and often imbalanced cocktails defined drinking culture in the 1970s. That, coupled with the timely invention of the first frozen margarita machine in neighboring Texas, set the stylistic and technological framework for the frosty boozy drink boom in the decade that followed.

From the neon-lit specialty shops that line Bourbon Street to the styrofoam cup-slinging drive-thrus in less touristy areas, the Big Easy — heck, much of the state of Louisiana, for that matter — is now awash in these highly potent, potentially brain-freezing fluids.

The climate is just right for it — both temperature-wise (think steamy and swampy) and politically (liquor lobby-friendly). Lax open-container rules in the city and a state law that specifically allows "frozen drinks" in cars have created a frosty go-cup haven that shows no signs of thawing.

The hot weather, festive atmosphere and loose regulatory environment surely helps to explain why the frozen daiquiri has become so popular in New Orleans. For a better understanding of how it happened, you have to look outside city limits.

Historian Mizell-Nelson, writing in Louisiana Cultural Vistas magazine, traces the roots of the daiquiri craze to a tiny mom 'n' pops liquor shop on the outskirts of Ruston, LA — a college town nearly 300 miles from New Orleans.

The story goes something like this: In 1979, proprietors Red and Hazel Williams were looking for a way to make use of unsold bottles of "Tequila Sunrise" mix, so they blended it with ice and offered the concoction as a sort of "impulse purchase" at the counter. The impulse proved significant. Demand was so great that the family moved on from conventional blenders to Italian-made frozen slush machines. Eventually, the couple's son, Dolph Williams, began manufacturing his own line of machines capable of handling even greater capacity. His company, Frosty Factory of America, would go on to equip scores of imitators who opened similar shops in Louisiana and beyond.

Real estate developer David Briggs was among those entrepreneurs inspired by and equipped by the Williams family. Using their machines, Briggs founded New Orleans Original Daiquiris in 1983. His Bourbon Street location, in particular, helped popularize the concept, by offering free samples to passing tourists. Other French Quarter operators may have served icy cocktails out of a regular blender before Briggs came to town, Mizell-Nelson notes, but not likely on the same industrial-type scale. According to its web site, New Orleans Original Daiquiris now has more than 30 locations in Louisiana alone, and another 20 outposts, under its sister Fat Tuesday brand, from Las Vegas to Philadelphia.

Video: New Orleans's Daiquiri Culture

Today, even more upscale establishments are beginning to embrace the icy libations, which otherwise tend to be typecast as the provenance of simple-minded youths, working-class stiffs and everyday quick-fix alcoholics. "[E]levated, epicurean" bar St. Lawrence, for example, now serves a Pimm's Cup-flavored daiquiri made with fresh lemon-lime juice and house-made cucumber syrup, as well as a rotating, seasonal fresh-fruit-based flavor. And, the team behind chef Nathanial Zimet's white-tableclothed Boucherie reportedly plans to relocate the restaurant and open a more casual daiquiri and wings spot in its place.

"I think they're actually becoming a lot more sexy," says Pelican Bay's White. "Initially, people kind of thought, 'OK, it's something young people drink, they're full of alcohol, you can get highly intoxicated and it's just not a good drink.' Lately, it's being taken to another level of drink artistry."

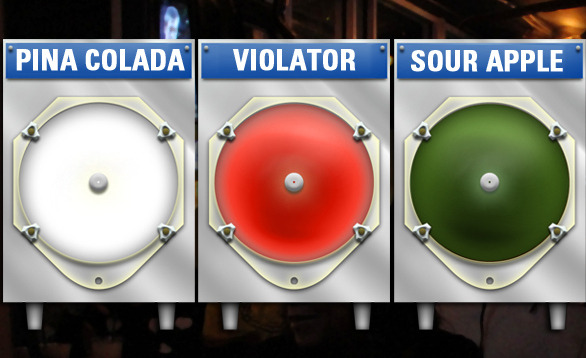

At Pelican Bay, for instance, White skips the standard jug of industrial syrup in favor of more crafty ingredients, including real vanilla milk and a "quality" 151-proof rum to make her signature piña colada daiquiri. To keep the milky tipple extra fresh, White further employs an ice cream machine instead of the traditional whirling daiquiri maker, she says.

Renewed interest in the frosty hooch is further evidenced by the recent emergence of the New Orleans Daiquiri Festival. Founded in 2011, the now-annual event was expanded from one to two full days last month and attracted an estimated crowd of 2,500. Organizer Jeremy Thompson says his passion for the frozen beverage was inspired by a visit to Gene's Curbside Daiquiris, a local favorite housed in a bright pink building, where the staff whips up its own homemade mixes and markets them under some striking names, such as the popular "What the F–K!" (The venue made headlines recently when pop-music power couple Beyoncé and Jay Z paid a visit.) "It was at Gene's that I had that kind of 'wow' moment – like, look at all these flavors, look at all these possibilities," Thompson says. "It's still my favorite experience, going to Gene's and sitting on the steps next door."

Thompson has come to view the daiquiri as an important symbol of New Orleanians' freedoms — "our right to drink outdoors," he says. As such, he thinks residents should work to protect it. Toward that end, this year's festival included an anti-litter message. Improperly discarded go-cups have triggered a bit of backlash against daiquiri culture in some New Orleans neighborhoods, Thompson explains. He's hoping to promote better alternatives to the throw-away non-recyclable styrofoam go-cups that dominate the city's daiquiri scene. Unfortunately, he notes, "there's not a lot of other things that do what [styrofoam] does that are cost-effective."

From a sociological perspective, Mizell-Nelson suggests that Louisianans are sort of groomed to become daiquiri devotees from an early age. "Children are weaned on sugary snowball treats in Louisiana before the sugar fiends graduate to alcohol mixtures," he tells Food Republic. "It may be some cultural connection between the region's past and present as one of the nation's largest sugar cane producers and sugar refining areas."

It comes as little surprise then that local daiquiri shops have become gathering spots for the young – "not unlike the milk bar in A Clockwork Orange," Mizell-Nelson notes. "The feeling or sensation of 'freedom' when you and your friends can drive through a daquiri shop and leave with gallons of drinks to go outweighs the fact that anyone of could make a better drink with his or her own blender."