This May Be The Rye Whiskey That Will Put Rye Whiskey On The Map

Rye is probably the friendliest member of the whiskey family. Less full-bodied than bourbon, not as smoky as Scotch, and often smoother than Irish whiskey, its caramel, vanilla and slightly fruity tones blend easily with almost anything — all while retaining a recognizable whiskey character. But rye's friendliness hasn't always paid off in terms of general popularity, and the liquor has rarely received the adulation enjoyed by other liquors.

One could even argue that rye's generous, low-key character has made it into the doormat of the liquor cabinet, the kind of easy-to-please friend who goes along with everyone else, rarely adding a unique character to the proceedings. For the most part, whiskey business is aggressive and opinionated: whiskey distillers are notorious for waging long-lasting wars of attrition over questions like where a "Scotch" whiskey can be distilled and what percentage of corn is necessary for a liquor to be called "bourbon." Meanwhile, rye – the only liquor actually named for its primary grain – shares its name with another booze that often doesn't contain rye at all: in many places, Canadian whiskey is generically known as "rye," even when the grain doesn't show up on the mash bill.

For decades, the only three ryes that were widely available on the market, Jim Beam Rye, Rittenhouse and Old Overholt, held a spot somewhere on the bottom shelf of the whiskey section in most liquor stores, but in the past few years, the whiskey has been slowly coming into its own. Beam and Overholt have been joined by a veritable avalanche of mid-level and upper-shelf brands, including Catoctin Creek (2009), Bulleit Rye (2011), and Knob Creek (2012). But while the resurgence of the liquor is promising, rye still remains on the margins, a nice mixer that usually isn't all that complex.

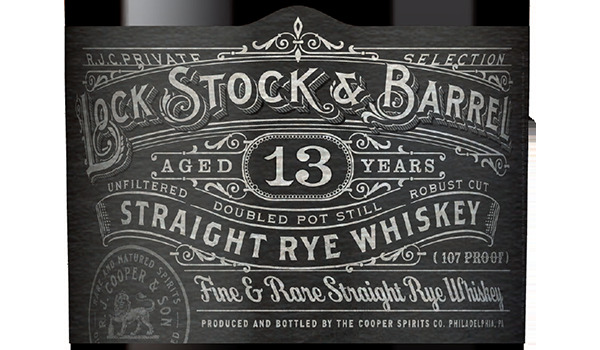

Given rye's low-key history, it isn't hard to see why many whiskey enthusiasts became excited earlier this year when Cooper Spirits, the company that produces St. Germain elderflower liqueur, announced that it was releasing a limited-edition pure rye spirit that had been aged for thirteen years. Patterned after Prohibition-era liquor, the new liquor, named Lock Stock and Barrel, has a nice historical connection linking it to rye's heyday: the raw spirit is produced by Alberta Distillers Limited, a Canadian liquor company that supplied American bootleggers during Prohibition. But if the spirit's origins are traditional, its treatment is not: the thirteen years that it spends in a barrel are a far cry from the 2-3 years that most ryes get.

Robert J. Cooper, Founder of Cooper Spirits, notes that age is one of the biggest challenges of rye. "When I first tasted the rye we used in Lock Stock and Barrel, it was nine years old" he recalls. "It was really abrasive. It needed more time to reach its full potential." At thirteen years old, he says, "it's still aggressive and challenging, but it's gotten a nice, rounded tone."

This limited run of 13-year-old rye, Cooper emphasizes, is only the first of several rye batches that Cooper Spirits have planned. A fifteen-year-old bottling, which Cooper will release next year, is especially promising, and he hopes to experiment with different barrel finishes, which will add even more nuances to Lock Stock and Barrel's ryes. "This is only the first of several aggressive, savage, intense releases that we have planned," he promises.

While Cooper touts the intensity of Lock Stock and Barrel, it still retains the relatively gentle rye character. Despite its daunting 101.3 proof level, the spirit is surprisingly smooth, with only a hint of the alcohol roughness that one would expect. But, while it has the familiar rye fruitiness and flavor, Lock Stock and Barrel has a far richer flavor than younger ryes like Rittenhouse or Jim Beam. It's almost as if the natural sweetness of most rye whiskies has been concentrated and amped up a notch or two.

On the other hand, that smoothness comes with a cost. After all, as anyone who has ever inflicted an Islay Scotch upon an unsuspecting friend or loved one knows, one person's "harshness," is another person's "character." In terms of flavor, even the comparatively rough edges on Lock Stock and Barrel come across as mild, particularly when placed next to non-rye whiskies. It isn't too smoky or too sweet, too peaty or too corn-roughened, too strong or too woody. It is, in the end, a remarkably friendly liquor.

Lock Stock and Barrel is a noble experiment, an exciting attempt to bring a neglected grain into the spotlight. But, ultimately, it only hints at rye's potential. And, having seen the beginnings of what a longer aging and a 100% rye bottling can do, it's exciting to imagine how the rest of Cooper's "savage, intense" rye releases will continue to reinterpret the grain.

Try out these rye whiskey cocktail recipes on Food Republic: