The Oldest Known Beer Recipe Is Made From Old Bread

Humans have been drinking beer for millennia. The Sumerians, a major early Mesopotamian civilization located in modern day Iraq, have left us with records of beer consumption dating back almost 5,000 years. This includes the world's oldest surviving beer recipe, which demonstrates an ingenious way to avoid throwing out up food scraps — specifically, stale bread.

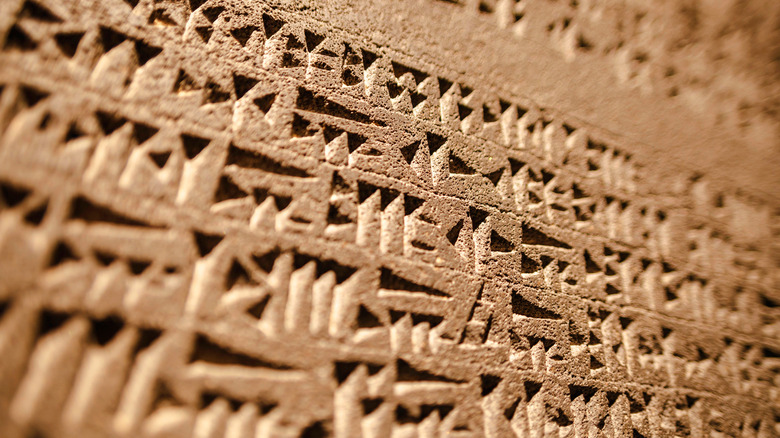

The recipe was written on a clay tablet around 1,800 B.C.E. The record isn't a simple list of steps and ingredients, however. Instead, it takes the form of a poetic ode to Ninkasi, the Sumerian goddess of beer and brewing (now serious beer aficionados know who to worship!). Known as "Hymn to Ninkasi," the poem extols the goddess as a master beer brewer (and notably, women were mostly responsible for Sumerian beer production). The tablet describes Ninkasi baking a barley-based bread called bappir, then fermenting the stale bread with sweeteners and malted wheat. The tale explains a rough recipe that modern beer brewers have tried to recreate.

This old distilling method is quite different from today's home brewing, so the beverage it produces ain't your average Bud Light. Modern recreations have a cloudy appearance and thick, foamy texture. They've been noted to taste less like beer as we know it today, and more like Russian kvass (a fermented bread-based beverage) or barley cider. The world's first beer also has a low ABV of roughly 2%, so the Sumerians could likely drink quite a bit at once.

A closer look at how the Sumerians brewed beer

The repeated mentions of bappir or "beerbread" demonstrate the importance of stale bread to the Sumerian beer recipe. The ancient people frequently dried the bread and stored it away, meaning they had plenty of the stale stuff to use up. The bread's barley content has been corroborated by chemically-tested residue found in pots from the same era.

After opening with lines praising Ninkasi more generally, the following verses of the poem essentially correspond to the first four days of the brewing process. It explains how Sumerians would soak wheat berries overnight and sun-dry them on reed mats to make malted wheat. They would then mix torn bappir with the malt and what the poem calls honey and wine (though this isn't as specific as it may sound).

Historians believe that what the Sumerians called "honey" in this context could also mean date syrup or a combination of dates and honey. Some translations even add the word "date" in front of "honey" in the fourth stanza of the poem. "Wine" might actually refer to grapes or raisins. To finish the ancient beer, the entire mixture (called "sweetwort") would ferment in a clay jar, and the alcohol slowly dripped into another clay vessel placed below. Sumerians did not filter the grain and bread from their beer, which is one of the reasons why they drank it with straws made of reed from a communal bowl.

More ancient beer recipes used today

Multiple breweries have tried their hand at making Sumerian beer, ever since the compelling tablet was first translated in 1964. The first attempt came in 1989, when San Francisco company Anchor Brewing teamed with a bio-anthropologist to make the ancient brew. The company deemed the result "drinkable," and didn't wind up selling the beverage.

In 2012, Cleveland's Great Lakes Brewery teamed up with archaeologists from The University of Chicago for their own attempt at the old recipe. The brewery went so far as to use clay pots modeled on archeological Sumerian models, as well as fermenting the beer in the sun just as the Sumerians would have. While the beer was, again, not meant for commercial use, it inspired a similar offering from a brewery called Gilgamash (named in honor of the legendary Sumerian king Gilgamesh).

In 2016, London-based brewery Toast Brewing approached the recipe from a new angle: a way to support food sustainability. The company saw the recipe as a way to repurpose the massive amounts of manufactured bread that normally get thrown out every year. They adapted the recipe to modern tastes to produce a brew meant to fight food waste: One for the Earth Pale Ale, described as earthy, spicy, and slight tropical. For curious drinkers or home brewers looking for something to do with stale bread, maybe it's time to pay tribute to where beer began.