Why Coffee Cost A Penny During The Enlightenment Period

According to a 2023 survey, more than half of Americans regularly consume coffee (via Statista). For many of us, it's the necessary start to a good day, the thing that motivates us to climb out of bed in the first place, or a ritual that punctuates our afternoons and brings as much comfort as the taste or effects of the drink itself. But long before caffeine dependence became a commonplace affliction that consumes a regular portion of our paychecks, the drink played a very different role in society — and cost a heck of a lot less, too.

During the Enlightenment period in England, people paid only a penny for their cup of coffee. A simple, weak beverage brewed in large pots, coffee was an inexpensive commodity since it was more broadly produced and easily accessible. In addition to their daily dose of caffeine, one penny bought café-goers access to newspapers, books, and an opportunity to engage in stimulating debate with diverse community members — regardless of social status. Because of this, coffeehouses during the Enlightenment were also known as penny universities.

The reason coffee was so inexpensive

While paying so little for coffee may surprise you, the other beverage options commonly available in 17th-century England may shock you more. Water in London was not safe to drink, so many drank lightly alcoholic beers, wine, and spirits in its place — the fermentation process killed off some of the harmful bacteria it contained. Other popular drinks required boiling water before drinking them, namely: tea, hot chocolate, and coffee.

Unlike tea, which had to be imported from China and paid for with silver, an increasingly rare currency during the 1600s, coffee was more accessible and easier to acquire. The coffee trade originated in Yemen in the 16th century, and Yemeni-style coffee is still popular in cafés today. The commodity spread to Southern India, Sri Lanka, and several East Indies islands, and trade was soon monopolized by the Dutch. With more production sites and trade opportunities, coffee was less expensive to procure. It helps, too, that — at least by today's standards — very little coffee was actually used to make the beverage. A 17th-century manual on how to prepare the drink instructs users to measure out only a third of a spoonful of coffee grounds for each cup (per The New Yorker). Inventory stretched much farther by using so little product to make the drink.

How the accessibility of coffee changed society

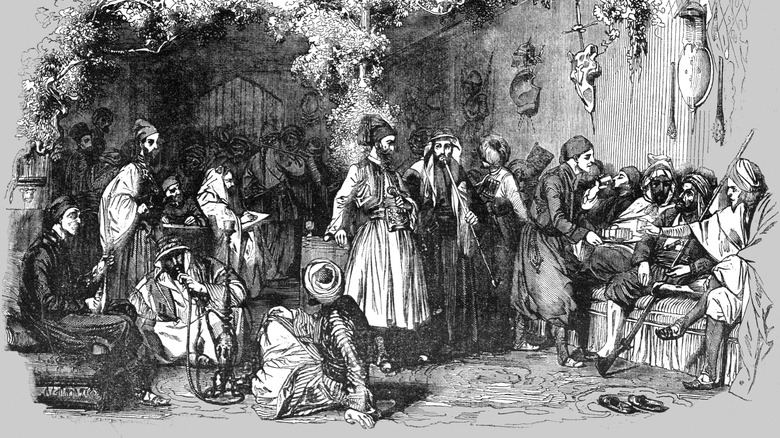

Likely originating in the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century, where alcohol was rare due to the predominance of the Muslim faith, the coffeehouse functioned as an egalitarian space — among men — for gathering, building community, and sharing ideas. This model arrived in England in the 17th century, and while we may associate the country with a dreamy afternoon tea, the affordability of coffee made it more popular.

For a single penny, citizens from all walks of life were welcome to read the latest news and engage with contemporary art and literature. Beyond having access to print materials, the coffeehouse provided a public space in which to share their perspectives in debates with their peers. In a hierarchical society like 17th century London, citizens had limited opportunities to interact with people outside of family, work, and religion, and access to education was strongly influenced by socioeconomic standing.

Not only did people find themselves in a revolutionary social and intellectual environment, but they did so while consuming a stimulant that increased focus and alertness, rather than becoming impaired by alcohol in pubs or taverns. Coffeehouses became popular sites of political, intellectual, creative, and social innovation, and the impact of the movements and institutions that emerged as a result can't be overstated. Just over 20 years after England's first coffeehouse opened, more than 3,000 were established around the country — more than anywhere else in the world.