Why Ancient People Hated The Taste Of Watermelon

It's difficult to imagine experiencing summer without eating sweet, refreshing watermelon. But, if the fruits enjoyed today tasted like they did 5,000 years ago in their native Africa, it would be unfathomable to imagine such things as watermelon mojitos and sorbets. Remnants and seeds of ancient watermelons have been discovered in more recent years in such places as Libya, Sudan, and Egypt. Testing and research has shown historians that these fruits were exceptionally firm, with pale flesh, and a bitter or bland flavor. Needless to say, they weren't a very popular food source, but that doesn't mean they weren't an important resource.

As the name suggests, ancient watermelons were lauded for their hydration abilities. Everyone from travelers to farmers to Egyptian pharaohs found them useful. Travelers used them for pseudo canteens for long journeys where they wouldn't have had easy access to water; farmers found them to be both a good water and food source for their livestock; and there has been evidence uncovered to suggest that watermelons were placed in pharaohs' graves so the rulers would have water during their journey to the afterlife.

But as far as cutting a watermelon open to enjoy during ancient Egyptian times, that was unlikely due to their unagreeable taste. It would be centuries before the watermelon as we know it (juicy, sweet, and red in color) would emerge.

What changed to make watermelon a sweet fruit?

Given the practice of taking watermelons on long journeys, it's easy to deduce how the fruit began spreading from nation to nation. Written documents from 400 B.C to 500 A.D. suggest that watermelon had spread to Mediterranean countries by that time period. What's interesting is, that by 200 A.D., evidence proposes that the spherical fruit was more palatable. Hebrew writings from Israel around this time categorized watermelons alongside figs, grapes, and pomegranates, all of which happen to be sweet. They also describe the melons as being yellowish in color. So, what changed along this long journey of time?

Cleary, brilliant scientific minds figured out that an element in the genetic code is what gave watermelon its bitterness, something that they and their descendants were able to gradually breed out. As the fruit's color was also determined by that single gene, the hue of the flesh naturally morphed as well. This is supported by an Israeli mosaic dating to about 425 A.D., which shows a fruit that looks strikingly similar to a modern-day watermelon with a yellow-orange color on the inside.

As the fruit spread throughout the Mediterranean, its uses transformed as well. While it was undoubtedly eaten, the Greeks also found it useful as a diuretic and for purportedly treating heat stroke.

The fruit's modern look and new uses

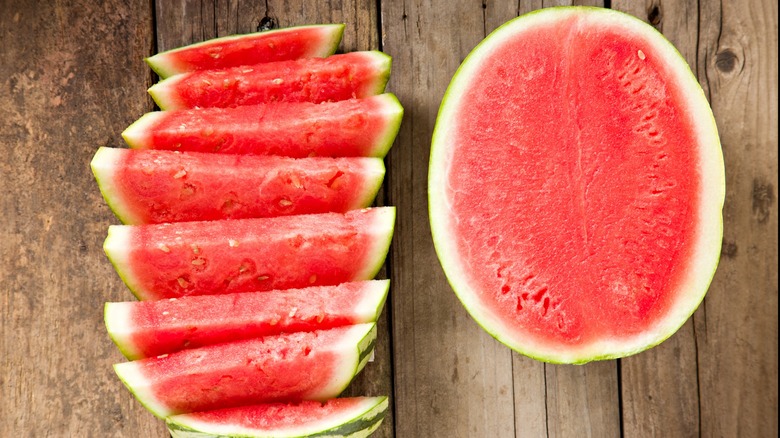

Today, there are an astounding 1,200 types of watermelon in existence worldwide, with around 300 of those grown in North and South America. Centuries of breeding have produced the melons people love so much. Today, they're colorful (mostly red, but not always) and sugar-sweet, and many varieties have been bred to be seedless, although "seedless watermelon" is a bit misleading. They can be as small as a softball and as large as a toddler, with flesh varying from white to deep crimson.

Surely ancient civilizations couldn't imagine cracking open a watermelon for fun and eating it for dessert. But that's exactly where we are at today (not to mention the fact that we're also using it to make pizza), which begs the question: Can future societies expect purple and watermelons that are as sweet as honey? Only time will tell.