The Failure Of Keedoozle, The Grocery Store Vending Machine

On September 6, 1916, Piggly Wiggly opened the world's first supermarket location in Memphis, Tennessee, revolutionizing the way people shopped for groceries by allowing them a self-serve experience where they could grab their own items from store shelves. Prior to this, customers would have to give clerks a list of items to retrieve for them.

The idea was the brainchild of Clarence Saunders, a former checkout clerk who birthed the self-service model. At this time in American history, grocery stores were smaller in size and more specialized in products, but to Saunders, the area most in need of change was the extra costs of all the clerks. By allowing customers to peruse store shelves themselves and hire employees for stock and checkout purposes only, Saunders cut costs yet didn't sacrifice convenience.

In a quest to outdo even that breakthrough, Saunders soon focused on a new project — a mechanical automation called Keedoozle that basically provided groceries in a vending machine format. Unfortunately for Saunders, neither society nor technology was quite ready for this type of shopping experience.

The real story behind Keedoozle

Keedoozle was a state-of-the-art pivot in the early 20th century but, in reality, it was more of a desperate last-ditch effort of Saunders to make money than a way of authentically expanding his supermarket empire. In 1923, Saunders got caught engaging in pre-Depression stock market manipulation and was cut off from publicly trading, forcing him to sell his Piggly Wiggly assets and his supermarket fortune. The ensuing Great Depression also deprived Saunders the chance of rebuilding his fortune, and he announced the idea for Keedoozle in 1936 in what he called his "final plunge" into the supermarket business.

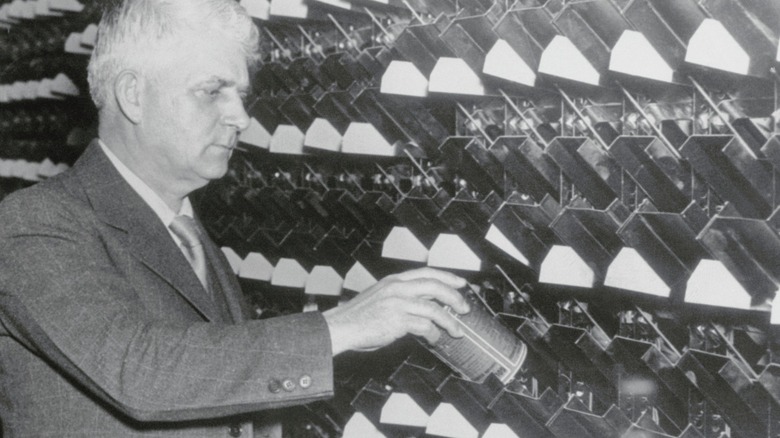

It's unclear if the name Keedoozle is either a fun way of spelling out "key does all" or a nonsense word that Saunders picked out at random, but the concept implies the former while the chaos of operations points to the latter. The way it worked was that shoppers walked around the store and viewed items through glass display cases, and would insert a key into a slot under each product they wanted to purchase. The keyholes would punch in patterns on ticker tape attached to the keys, which cashiers then inserted into a reader to send signals to a conveyer belt, a la a giant vending machine. If this systems sounds complicated for 1936, that's because it was.

Keedoozle was years ahead of its time

Technical issues plagued Keedoozle almost from day one. The conveyer belts often couldn't keep up with the rush of customers during peak hours, and the electric signals weren't precise enough to get every order right. Clerks still were needed for the operation, too, as humans had to load the conveyor belts behind the scenes. It was here, in one of Keedoozle's earliest test runs, that a reporter was almost crushed under a spilled pile of canned turnips. Ironically, the cost of Keedoozle was also too high to compete with self-service supermarkets since the technology was more expensive to upkeep.

Keedoozle came off the market in 1949, draining Saunders of a then-whopping $170,000 fortune. Not one to take a loss easily, the inventor blamed Keedoozle's failure on the customers, proclaiming that his concept was "too much for the average brain to comprehend." Despite his bitterness, he was truly ahead of his time. Companies like Amazon have been attempting to integrate more automation into grocery shopping, and although customers still pick up items off of shelves without the use of futuristic concepts like Saunders' conveyor belt and keyhole system, Kroger's robotic delivery system sounds pretty darn close. Supermarkets wouldn't be what they are today without Saunders; perhaps his more far-out ideas could find a place in the near future.