If You Put Sugar In Your Cornbread, You're Not A True Southerner

First, let's get this out of the way: Only true Southern folks can answer questions about genuine down-home Southern cornbread. Sure, there's a Northern version, but where I come from, we call that cake, not cornbread. The distinguishing reason is that North of the Mason-Dixon, cornbread is routinely sweet. Real, traditional, Southern-style cornbread is savory, not sweet, and always has been. It also employs more cornmeal than flour, making it flatter and less "cakey." Take that from a gal born and raised (aka "bone and razed") in the Mississippi Delta, dubbed "the most Southern place on earth," per the National Endowment for the Humanities.

In the deep, deep South, cornbread is a standard, savory meal component, staking a claim on supper tables right next to bowls of steaming chili or plates of spicy barbecue. But it doesn't have to be a special occasion; it can accompany any type of meal, any time. In fact, savory cornbread, corn muffins, or even old-fashioned "corn pones" can sometimes be the meal all on its own, maybe with some collard greens, butterbeans, yellow summer squash, or fried okra, plus a tall glass of frosty-cold iced tea.

Sweetening a pan of cornbread would be like mixing sugar in black-eyed peas or sprinkling it over fried chicken — it's just not done, at least in traditional cooking. Mind you, there are plenty of ways to jazz up regular cornbread, including stirring in jalapeños, buttermilk, bacon, chives, or even corn kernels. But sugar? Nope. And there are some way-back reasons for that.

Sugar was a rich man's food

Southern history is complex, weaving its way through the Civil War, an exit from slavery, post-war Reconstruction, and the Civil Rights movement. On varying levels, they all inform food culture in the deeply Southern parts of America — including cornbread. For example, newly freed enslaved people often struggled to earn a living, and sugar would have been costly for those re-inventing life in a new-to-them world. It was a prized commodity that only became prevalent and affordable in the late 1800s and early 1900s, after America's treaty with Hawaii gave access to island sugar plantations.

Enslaved people's meager cabin kitchens were not supplied with sugar, but cornmeal was cheap, requiring only water, some flour, and a bit of salt to make a tasty meal. After the Emancipation Proclamation, many former enslaved people eventually took jobs as domestic help in wealthier households, including cooking the family meals. You can imagine what comes next: cornbread on supper tables across the South, with no sugar. Generations grew up knowing this as "real" cornbread.

Old-fashioned cornbread recipes are also considered comfort foods, on many levels. In an essay for The New York Times, opinion writer Margaret Renkl recalls generational ties of making cornbread in her 1960s Alabama youth. All these years later, she states, "Whatever else is happening outside my windows, whatever struggles are still ahead, just the sight of that golden disk of buttery goodness can make me feel a tiny bit better."

Cornbread in Native communities

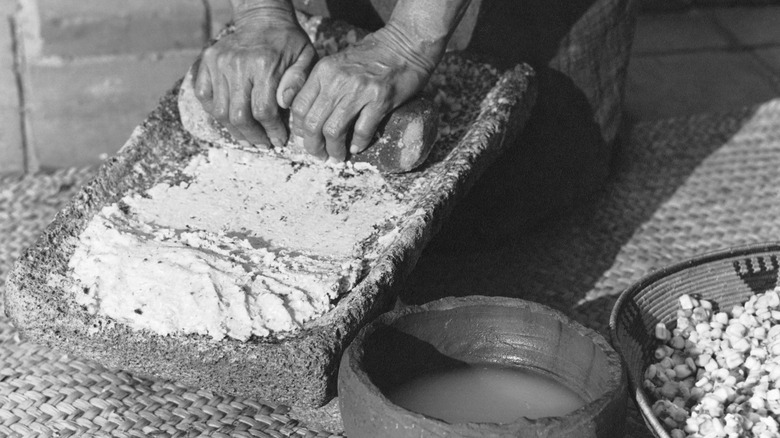

It's important to note that cornbread wasn't invented in the American colonies — far from it. Native Americans were growing corn well before European settlers arrived, and they even taught them how to dry and grind the corn into meal for making forms of cornbread and fried corn cakes — using only corn meal, water, and salt. Again, NO sugar! These communities also created lesser-known versions, still favorites in parts of the American South, known as "corn pones" and Johnny cakes (an adaptation of "journey cakes," because they survived long journeys.)

The evolved version known as Southern cornbread, which still reigns today, invariably involves a cast-iron skillet, preferably black, well-seasoned, and handed down from one generation to the next. But don't worry; if that's not a thing in your family yet, you can certainly start the tradition now, regardless of where you live. The skillet gets heated first on the stovetop with a bit of oil, which for many years was bacon grease, imparting a unique (and I must say, delicious) flavor, but any kind of cooking oil works just fine.

After the oil starts to shimmer, pour your unsweetened cornbread batter into the sizzling-hot skillet, and let it gently crackle and fry for a few minutes. This creates the crispy, crunchy sides and bottom. Then just transfer the cornbread, skillet and all, to a hot oven, and let it bake until the top is golden brown and the inside is fully cooked.

If you must sweeten, just use honey

It's worth mentioning that newer generations, even those in deep Southern pockets of the country, are more exposed to experimental cooking and cultural cuisine than their predecessors. If they're willing to bear the shame of slipping a tad of sugar into their cornbread batter, things could incrementally change.

But generally, the no-sugar rule still stands. Those who really need a surge of sugary flavor can, for goodness sake, just add some honey or sorghum molasses after the fact. Or keep things pure by satisfying the sweet tooth with a slice of pecan or lemon icebox pie for dessert.

It's no accident that the deeply deep-South state of Tennessee still hosts the National Cornbread Festival every year, and the sponsors are Southern neighbors: Lodge cookware, famous for its cast-iron skillets, and Martha White Corn Meal, which, obviously, contains NO SUGAR. In other words, real cornbread.