Which Cheeses Are Naturally Lactose-Free?

Lactase is not a superpower, but it does have one very important function: It breaks down lactose, the sugar found in dairy milk and therefore in cheese. Those suffering from lactose intolerance lack this vital enzyme, resulting not only in physical discomfort, but more significantly, the uniquely profound emotional distress that comes from never being able to eat cheese.

Hope is not lost, however! Brands like Norway's Jarlsberg and Cabot Creamery from Vermont boast that their cheeses are "naturally lactose-free." Milk is chock-full o' lactose, so how is that possible? Are they using magical cows?

As it turns out, no, sorry — no magical cows. Milk from ordinary livestock is more than sufficient. Most of the problematic lactose is either removed or converted into more easily digestible forms during routine cheesemaking processes. "The cheesemaking process isn't altered to make lactose-free a reality. It's just part of the science of making [our] cheddar," explains Nate Formalarie, communications manager for Cabot Creamery. For those with a dairy allergy, this unfortunately isn't much use. However, for those who battle intolerance, there is a wide array of pungent, creamy, salty, crumbly and digestion-friendly cheese goodness out there. So go ahead, order the burger. Cheese yo'self.

Whey

To make cheese, typically an edible acid like rennet is added to milk, which forces the liquid to curdle and form curds. Whey is the liquid remaining after the milk has been curdled and strained. To make cheese, the curds are separated from the whey and then, depending on the variety of cheese, are ripened and aged. "Most of the lactose follows the whey," explain the cheesemakers from Jarlsberg. "Very little lactose is left in the curd," which, after ripening, becomes the final product available in stores.

Aging

During the ripening process, cheesemakers add probiotic bacteria like lactobacillus to the cheese. The bacteria contain high concentrations of lactase, which starts breaking down and eventually fermenting the lactose, converting any remaining milk sugars in the curd into easier-to-digest lactic acid. How these bacteria interact with the cheese not only affects its taste and consistency, but in a fully matured cheese, will convert nearly all of the lactose. In many cases, the bacteria will fully consume the lactose, leaving behind delicious, creamy cheese with trace amounts of sugar.

Many people with lactose intolerance can eat certain cheeses, yogurt and other fermented dairy products because of the high content of active bacteria cultures. It's not uncommon for European meals to conclude with a cheese course, too, for the digestive benefits of the probiotic bacteria and fermented sugars found in most cheeses. Shockingly, even the gooiest, triple-cream Brie and Camembert are not off limits. They average a lactose content of less than 2 percent. For a handy guide, refer to Steve Carper's Lactose Intolerance Clearinghouse. Despite the silly name and seriously outdated web design, Steve really knows his stuff.

As a general rule, the longer a cheese is aged, the more time the bacteria have to break down the remaining sugars, resulting in lower overall lactose content. For those with sensitive stomachs, heavily aged cheeses like Manchego and Parmigiano-Reggiano, which are often aged for at least 18 months, can usually be eaten without regret. Cabot ages its cheddars for anywhere from three to five years.

Danger! Danger!

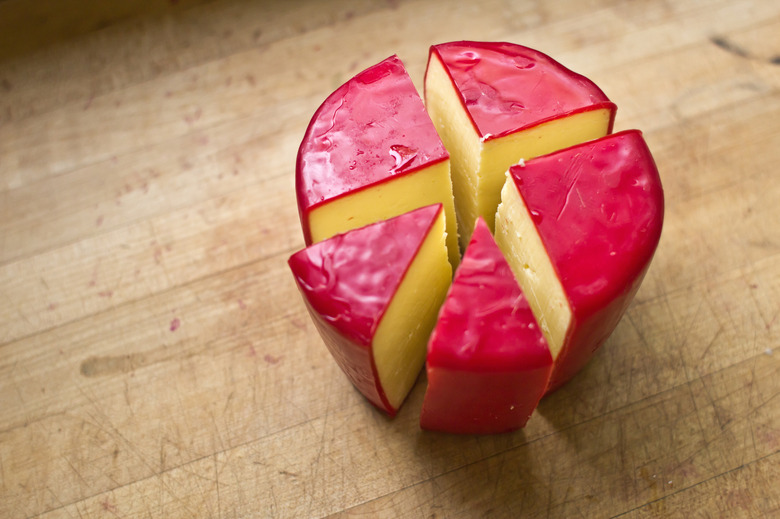

The simple fact that a particular cheese may be low in lactose (hello, dearest Gouda) doesn't give you carte blanche to go on a cheese bender. Serving size matters. Depending on the level of sensitivity, most people with lactose intolerance can enjoy up to 2 percent lactose content. Also be mindful of combining forms of dairy. Milk is higher in lactose (up to 5 percent), and many recipes, like rich macaroni and cheese, rely on large amounts of both milk, heavy cream (4 percent lactose) and butter in the béchamel sauce. Certain crackers and baked goods, too, use milk and/or cheese powders that are significantly higher in lactose.

Fresh cheeses like mozzarella, ricotta and feta, which are not aged at all, should be avoided. Even American cheese and Velveeta, despite their reputations for being a heavily processed faux "cheese product," contain anywhere from 9 to 14 percent lactose.

Author's note: Upon researching this piece, the lactose-intolerant writer immediately procured an unnecessarily large wedge of imported Camembert. The results were thoroughly delicious and without gastrointestinal consequence.