All You Need To Know About Dried Chiles

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

In Cook's Science, the all-new companion to the New York Times best-seller The Science of Good Cooking, America's Test Kitchen deep-dives into the surprising science behind 50 of our favorite ingredients.

Each chapter explains the science behind one of the 50 ingredients in a short, informative essay — topics including pork shoulder, apples, quinoa, and dark chocolate — before moving on to an original (and sometimes quirky) experiment performed in their test kitchen and designed to show how the science works. Love some heat in your food? Lots of it? Or can you not stand it? Here's the book's study on dried chile peppers.

How The Science Works

Peppers are the fruit of plants belonging to the genus Capsicum, which includes mild sweet peppers like bell peppers, and hot, spicy peppers commonly called chiles or chili peppers. Like tomatoes, peppers are a member of the nightshade family, botanically named Solanaceae.

Peppers originated in the Americas and were first domesticated as a food more than 6,000 years ago in Mexico; though evidence shows they have been part of the human diet for almost 9,500 years. Christopher Columbus is given credit for first calling them "peppers," when he realized they could serve as a substitute for the much more costly, rare black peppercorns. Today, India is the world's largest producer of peppers.

The characteristic flavor and aroma of all peppers is largely due to a group of compounds called pyrazines—namely, one called 2-isobutyl-3-methoxypyrazine. Pyrazines are naturally formed in the tissue of the fruit as it ripens, so chopping and chewing are not necessary for the formation of pepper flavor. Pyrazines are among the most potent aroma compounds, with extremely low odor thresholds; humans can detect some of these compounds dissolved in water at concentrations as low as a part per trillion. In fact, bell and jalapeño peppers have been found to contain levels of only a few nanograms (or billionths of a gram) of 2-isobutyl-3-methoxypyrazine per gram of dried pepper.

Related: I Ate A Carolina Reaper Pepper And Lived To Tell The Story (Video Included)

Chile peppers owe their heat to a family of compounds called capsaicinoids. At least 12 different capsaicinoids have been identified in hot peppers, but two compounds, capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin, account for about 90 percent of the heat, both having similar potency. (The capsaicinoids are produced in the cells of the white pith, and migrate to the nearby seeds.) Capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin have been shown to bind to a specific receptor in the mouth — called the TRPV1 receptor, which is the capsaicin receptor — responsible for detecting pain in mammals. This pain is called a "chemesthetic sensation," a description that also applies to touch and heat and is different than taste or smell. Not all animals possess the same taste and smell receptors as humans, but chemesthetic receptors are widely distributed throughout the animal world.

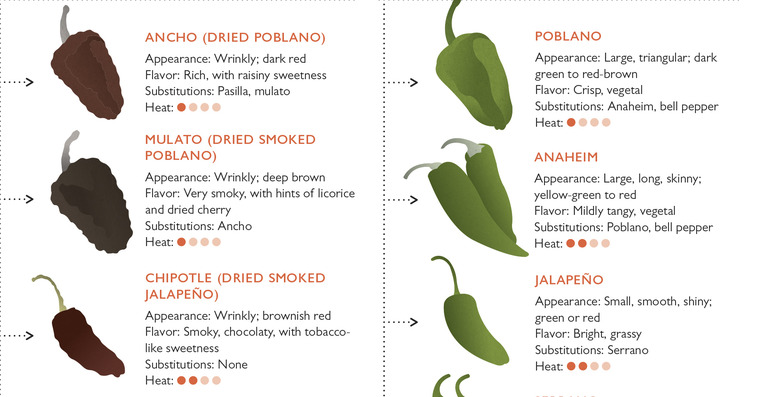

Drying a chile pepper reduces the weight of the pepper and therefore increases the relative hotness of the dried pepper by as much as 10 times. In addition, slowly drying peppers with heat, such as in the oven or a food dehydrator, increases the rich, sweet, raisin-like flavor characteristics of peppers, due primarily to the formation of 2-methylpropanal, 2-methylbutanal, and 3-methylbutanal. Smoking is another drying method, which adds the complexity of smoky flavor, like that in chipotle peppers. Generally, whole dried pods retain more flavor than crushed pods. Drying chiles results in a decrease in green, floral notes due to the loss of volatile compounds such as (Z)-3-hexenal and hexanal.

We make good use of dried chiles in the test kitchen, often toasting them and grinding them ourselves to create flavorful, fresh rubs or marinades. We use guajillo chiles to create the base of a marinade for pork in our spicy Tacos al Pastor, and New Mexican chiles to create a rub for our grilled steak. We toast (to bring out the best flavor), seed (to remove some heat), and purée a mixture of dried chiles for two very different types of chilis: our ultimate beef chili and our ultimate vegetarian chili.

Test Kitchen Experiment

Chiles get their heat from a class of chemical compounds called capsaicinoids, the most important of which is capsaicin. Capsaicin binds to receptors on our skin and tongue and causes a temporary burning sensation in even minute quantities. This pain response adds complexity to untold dishes and cuisines, but it's not always welcome. Anyone who's seeded chiles without gloves or gotten a bigger hit of spicy food than expected knows that sometimes all you want is relief. There are plenty of purported home remedies for cooling the burn, but do any of them actually work? To find out, we ran an unusual experiment.

Experiment

We rounded up some brave testers to seed chiles without gloves, smear chile paste onto patches of their skin, and eat scrambled eggs doused in hot sauce. On these affected areas we tested a number of home remedies. For the skin, we washed with soap and water, and rubbed with oil, vinegar, tomato juice, a baking soda slurry, and a 3 percent hydrogen peroxide solution. For the mouth, we asked tasters to swish with (but not swallow) water, whole milk, 5 percent alcohol-by-volume beer, and a 1.5 percent hydrogen peroxide solution.

Results

All testers noted that soap and water helped lessen the burn on their skin slightly, while rubbing oil, vinegar, tomato juice, or baking soda on their skin didn't help at all. As for their mouths, water and beer failed to lessen the burn, too. Milk, on the other hand, had a slight impact. Interestingly, the hydrogen peroxide treatment was deemed effective by a majority of testers at reducing the burning sensation both on the skin and in the mouth.

Takeaway

Why does hydrogen peroxide work? It turns out that it has the ability to oxidize capsaicin to a compound that does not readily bind with pain receptors. Hydrogen peroxide's oxidizing activity has been shown to increase in the presence of a weak alkali, such as sodium bicarbonate (baking soda). With some further testing we found that a solution of 1 tablespoon of 3 percent hydrogen peroxide, 1 tablespoon of water, and 1/8 teaspoon of baking soda worked best as a wash for the affected area or as a mouthwash (swish vigorously for 30 seconds). Toothpaste containing hydrogen peroxide and baking soda proved a somewhat less effective remedy. It's important to note that while the burn of capsaicin in your eyes can be very painful, you should not use hydrogen peroxide or baking soda (or toothpaste!) on your eyes — use warm water instead.

Excerpt from Cook's Science: How to Unlock Flavor in 50 of Our Favorite Ingredients by the Editors at America's Test Kitchen.