Is There A Future For The Classic Greasy Spoon Diner?

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Author Ed Hamilton fondly recalls his first time in an old-school New York City diner. "It was just called Donuts Sandwiches," he says. "I think it had another name, but it just said 'Donuts Sandwiches' — not 'Donuts & Sandwiches,' just 'Donuts Sandwiches' — on a real big sign."

Not a fancy place, certainly, but it had character, with a double horseshoe-shaped counter and classically gruff waitstaff. And it was cheap! "Two doughnuts and a coffee was a dollar," Hamilton says. "A hamburger and fries was $2.95.... Two people could eat for under $10. It was great!"

This was back in the 1990s, of course; suffice to say, a restaurant that affordable no longer exists in luxurious modern Manhattan. "Such a shame," says Hamilton, noting that the storefront has turned over multiple times since then. "I don't know what the hell it is now," he says.

We've come to La Bonbonniere, a similar greasy spoon kind of place (and one which, fortunately for our purposes, still clings to life along Eighth Avenue in NYC's Greenwich Village), to lament the decline of diner culture in the city. The place has all the markings of an archetypal American diner: worn floors, kitschy decor, large laminated menus offering a dizzying multitude of food options and big windows providing great views of urban life outside. (One notable exception: The restaurant closes daily at 7 p.m.; most traditional diners stay open late, if not all night.)

La Bonbonniere also makes a surprisingly good meatloaf sandwich. "Yeah, it's pretty tasty, isn't it?" says Hamilton, eyeballing the moderate drizzle of gravy on mine with a hint of envy. "I could have gone for the gravy, too, since they didn't put so much on, but I don't like it when they drown the whole thing and you can't pick it up."

An October report by Crain's New York suggests there are now fewer than 400 of these types of restaurants left in the city — down sharply from an estimated 1,000 only a generation ago. Just last week, the refreshed Empire Diner in Chelsea abruptly shut down, proving that it takes more than just a bold-name chef (Amanda Freitag) and a contemporary spin on diner classics (Reuben spring rolls, anyone?) to make this old-fashioned style of eating seem relevant again.

The diner downtrend dovetails with the theme of Hamilton's new book, The Chintz Age: Tales of Love and Loss for a New New York, which follows a series of working-class bohemian-type characters (actors, artists, authors and one curmudgeonly operator of an ill-fated underground bookstore) and their struggles to maintain a foothold in this increasingly expensive metropolis. In one scene, an aspiring Shakespearean actress takes refuge at an unnamed diner in downtown Manhattan following a troubling discovery about her boyfriend. There, "beneath florescent lights in a green vinyl booth," she huddles with her closest confidantes about what to do next. At least until some old Greek waiter interrupts to ask if she's ever going to order anything.

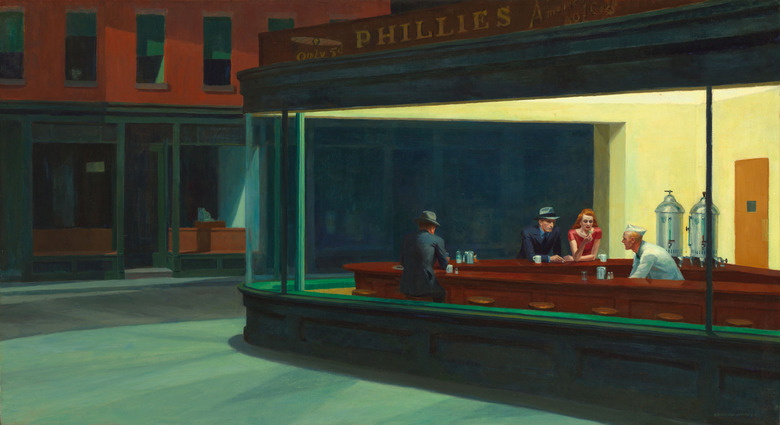

American pop culture is rife with scenes like this, as diners have provided a familiar backdrop for numerous movies and TV shows, from the opening (and ending) robbery sequence in Pulp Fiction to the successive servings of cherry pie on Twin Peaks and the countless kvetching sessions on Seinfeld. Heck, you might even have some cheap print of an iconic diner scene hanging on your wall at home: the ubiquitous Nighthawks, the late New York painter Edward Hopper's most famous work, depicts what the artist himself described in his notes as a "cheap restaurant," outfitted with fluorescent light, round bar stools and white coffee mugs in traditional diner fashion.

Why did this sort of working-class restaurant become so ingrained in the American imagination? Hamilton offers a few thoughts: "Because they're cheap, and they're always open, they're always welcoming," he says. "Diners can be noisy, but usually they're kind of relaxing. It's just like people's living rooms or dining rooms. It's kind of like a home away from home, especially when people don't have enough space. Look at my little apartment; we couldn't even be having this conversation face-to-face, really."

When he first arrived in New York nearly 20 years ago, Hamilton ate a lot of his meals in diners. "Because I was always broke," the Louisville, Kentucky, native says. He was particularly fond of Eisenberg's, another NYC stalwart featuring exceptional corned beef sandwiches and, at one time, somewhat flexible pricing. "There was a guy who worked there, I remember, who thought the prices were too high, even though they were pretty low, so he would just charge you whatever he thought you should be paying," Hamilton says. As of today, Eisenberg's is still standing, but the laissez-faire billing system is long gone.

Not everyone is so nostalgic about these places; Hamilton suggests that's part of the problem. "I think that's the way it is with a lot of people who've come to the city recently, a lot of young people — they've never gotten into the habit of eating in diners," he says. "Maybe that's why they can't sustain their customer base anymore."

Well, that and the grim economic realities of doing business in the big bad city. Consider how places like La Bonbonniere must have to adjust their modus operandi just stay in business amid the rising costs of everything. Our modest lunch, which included two meatloaf sandwiches, a shared plate of french fries, one coffee and one iced tea, set us back a total of $35, plus tip. So much for the "cheap restaurant" experience of yore.

Is there a future for the old-fashioned diner in this city? And for that matter, what about the artists and writers these places have sustained and inspired through the years? That's sort of the whole point of Hamilton's book. "The tone is kind of bittersweet and nostalgic, but I also think it's forward-looking," he says. "It's people who have to decide whether to wallow in the past, and whether to give up and be old and say, 'My life is over,' or whether to carve out a place for themselves in whatever future we end up with."

Hamilton describes the book a sort of "prayer for resistance." Or, at least, entrenchment: "Maybe they don't have the stomach for activism or whatever, but people can still hold on to their little place in New York and wait for the cycle to come around, or wait for the fallout from all this crazy gentrification to settle, and then see what society we're going to be in when its done," he says.

With any luck, there will still be a few diners left to feed the holdouts, and when that happens, don't skip on the gravy.

Author Ed Hamilton reads from The Chintz Age at 7 p.m. on Friday, January 22, at Bluestockings Bookstore, 172 Allen St., New York, NY; and at 7 p.m. on Thursday, January 28, at Upshur Street Books, 827 Upshur St., Washington, D.C.