We're Now Comfortable With Spending $50 — Or $500 — On An Omakase

In June, Food Republic is counting the many reasons to love Asian food in America right now. Here's one of them.

"Let's go for an omakase this weekend." It may not be quite as catchy a phrase as "sushi with the girls," but it's certainly one that's been popping up more and more lately. Sushi tastes have seen a steady transformation in the United States since the 1990s and early 2000s, years dominated by the California roll and the spicy mayo-laced tuna roll. It's only been in somewhat recent times that the dining masses have opened their minds — and their wallets — and embraced the traditional Japanese concept of omakase. This shift is a result of people being curious about expanding their sushi knowledge: They don't only want to try Santa Barbara sea urchin; they also want to know exactly how it differs from its Japanese counterpart. Their willingness to learn has gone hand-in-hand with a number of omakase-only restaurant openings and increased attempts to adapt these offerings to appeal more to the American palate.

Originating from the Japanese word makaseru, which means "to entrust," omakase best translates to "I'll leave it to you." There are a few aspects of an omakase meal (the term is not used exclusively for sushi) that are rather irregular to the American diner. First, the selection of items served is left entirely to the chef, who may base his or her decisions on the freshest ingredients available that particular day, as well as a diner's personal preferences. It's akin to a tasting menu — without any sort of menu — and there's an element of surprise in play that is certainly part of the whole experience. Then there's the breakneck speed at which a traditional omakase meal can take place. Sit at the sushi bar and you might be out the door (and out of hundreds of dollars) a mere half hour later.

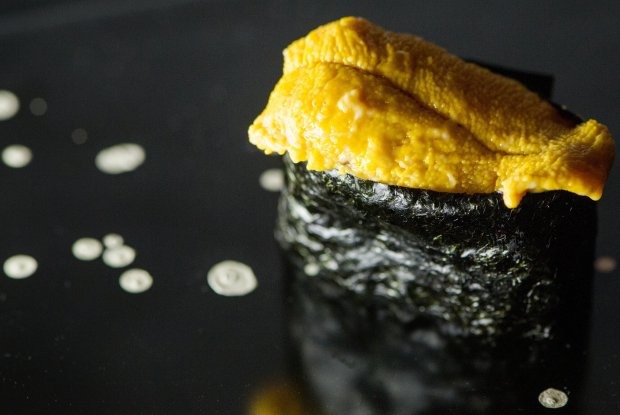

Just how has this type of meal increased in popularity in the U.S.? "As sushi knowledge proliferates, people are willing to pay more for an authentic experience," says David Gelb, the director of Jiro Dreams of Sushi, the acclaimed 2012 documentary that helped spread the idea of traditional Tokyo-style sushi, effectively mainstreaming the term "omakase" in the U.S. "People are beginning to realize that there is so much more to sushi than spicy tuna rolls." Sushi-based omakase meals often include delicacies such as sea urchin, fish roe and raw — or live — shrimp. Translation: We're not in California-roll land anymore.

Meanwhile, restaurants in major U.S. cities have begun to reflect these acquired tastes. Diners debate the various merits of a handful of omakase-only joints in Los Angeles, such as Urasawa, Sushi Zo, Q and Nozawa Bar. Many of these have opened in the past few years. Investment bankers and A-list celebrities jostle each other exactly one month in advance for a spot at Shuko in New York City, a new 20-seat sushi bar that offers a choice of just two set menu options. In his review for The New York Times, critic Pete Wells wrote that chefs Jimmy Lau and Nick Kim "have taken all the preciousness out of omakase and replaced it with a relaxed, sophisticated cool." Omakase: certified cool.

There has also been an increased amount of interest in omakase at establishments that invite — but do not require — one to trust the chef. "Even in restaurants where you can order à la carte, I've noticed people ordering omakase or asking about it," notes Gelb. In keeping with Japanese tradition, the majority of omakase-focused restaurants Stateside excel in simple approaches: There's often little more than a sushi bar, a small number of chefs and perhaps a few tables to be found.

There are, of course, exceptions to these general rules. French-Moroccan chef David Bouhadana's Sushi Dojo in Manhattan's East Village serves up one of the city's finest (and most affordable) omakases, and you're likely to throw down a sake bomb or two with the chef while disco music blares in the background as you receive a piece of pristine, lightly torched toro.

"Like anything from overseas, it will lose itself in translation, so that word [omakase] is already dead to me," decrees the animated chef. "Here in the States, we have to deal with allergies, dietary restrictions, kosher, gluten-free...so basically that word has no power." The chef specifically mentions that he feels responsible for attracting the younger generation — not necessarily your typical omakase consumers — to this type of cuisine. Bouhadana's lively two-year-old sushi den functions essentially as an accessible adaptation of the classic Japanese meal, a testament to omakase's ever-increasing popularity.

So has getting a group together for omakase become as casual and commonplace as grabbing beers with colleagues after work? Let's not get too ahead of ourselves just yet. There's still that whole it-can-cost-hundreds-of-dollars thing. But as long as diners' palates continue to expand and master chefs continue to open personal homages to omakase around the country, it's hundreds of dollars that more and more people will consider well spent.