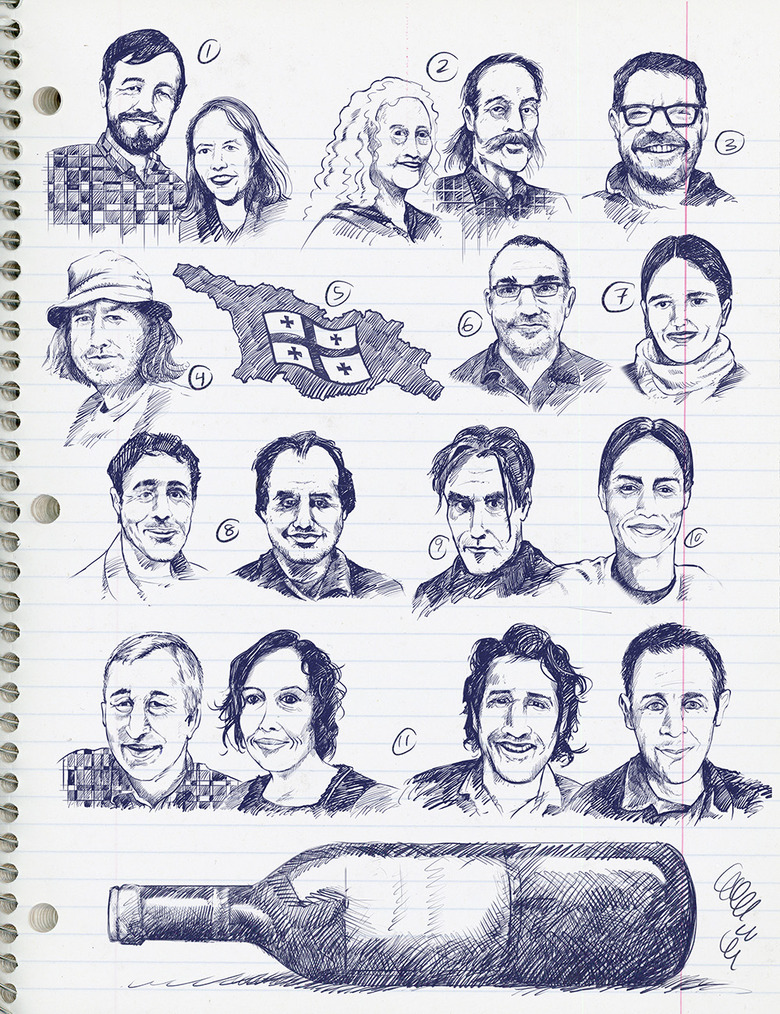

16 Important Names To Know In Natural Wine (Plus An Entire Country)

"Natural wine" is something of a polarizing term. To purists, it represents the ultimate viticultural pursuit — farming the grapes and fermenting the wine with no outside interference. To pragmatists, it denotes a noble idea that's just not practical: leaving wines in their natural state leaves too much room for error. (For the uninitiated, here's a link to a primer on natural wines.)

Whichever side you fall on, if you've even chosen sides, it's undeniable that natural wines are gaining momentum. In major cities like Paris and New York, wine bars and restaurant wine lists focusing on natural, biodynamic and organic wines are becoming increasingly prevalent. There's even a Natural Wine Week, which runs in NYC from February 26 to March 3 (more info on that here) and features tastings, dinners and classes.

One of the things I've noticed when ordering natural wines at some of the high-profile natural wine–focused spots — Le Verre Volé in Paris; Fish & Game in Hudson, New York; Racines NY and Compagnie des Vins Supernaturels in Manhattan — is that the sommeliers and chefs tend to reference specific producers when recommending new wines. Finding myself unfamiliar with most of these names, I asked Food Republic wine writer Chad Walsh to break down some important people to know. He came back with a list that doesn't weigh as heavily on French or Italian winemakers as I'd have imagined (and Spain's natural-wine scene isn't represented here), and it includes a surprising group of American winemakers — not to mention a whole country — and he's quick to point out that this is less a definitive list than a selection of winemakers he's following closely. It's also a good start to increasing your natural-wine knowledge. —Richard Martin

1. Tracey and Jared Brandt of Donkey & Goat

After quitting their jobs in electronic gaming, American husband and wife Jared and Tracey Brandt went to Europe to follow their passion: wine. They worked at various wineries, then spent an entire harvest in France with Éric Texier (see number 6 below). There, they learned the techniques that have helped to define their manifesto, which includes no inoculation of yeast, no fining or filtration, and even shunning plastic in their winery, which they decided to locate in Berkeley, California, convenient to the vineyards they work with in Mendocino and the Sierra Nevada Foothills.

Some of the early examples from Donkey & Goat were a little up and down, but everything I've tasted from 2012 shows a clarity, both figuratively and literally, that may once have been missing. Their largest-production cuvée, which is merely 600 or so cases, is an homage to Châteauneuf-du-Pape called 513, referring to their ability to source five of the 13 varieties allowed to be used in the orginal appellation. Dense, like great old-world Grenache-based wines, it still shows an exuberance of fruit and acidity that is decidedly new.

2. Debra Bermingham and Kim Engle of Bloomer Creek

The natural winemaking movement in the United States is by no means limited to California — Kelley Fox and others are doing amazing things in Oregon — and even extends to the Finger Lakes of upstate New York. There, Kim Engle is trying to make wines as naturally as he can, with the help of his artist-turned-vigneron wife, Debra Bermingham. Located on the eastern side of Seneca Lake, Bloomer Creek is not technically biodynamic, or even organic, but they're trying. Because of the moisture inherent to the region, avoiding mildew and other rot issues is difficult without synthetic sprays, but in cellar Engle is as natural as possible. Unlike most of his neighbors, he allows all of his fermentations to happen naturally and only adds sulfur at bottling.

Although the Rieslings are stellar, his Edelzwicker, an Alsatian-style blend of Gewurztraminer and Riesling blended with the less glamorous local favorite Cayuga White, is super-affordable, and the Cabernet Francs have a similar appeal to naturally inclined examples from the Loire.

3. Hardy Wallace of Dirty & Rowdy

Hardy Wallace, who we already profiled as someone you need to know in the American wine scene, may not yet be releasing the best wines on this list, but he's become an outspoken champion of natural winemaking. He is still beholden to growers who may or may not be working organically, which may make his wines unequivocally unnatural depending on your perspective, but he has embraced a lot of natural winemaking techniques in the cellar, like skin contact and natural fermentation in concrete eggs.

His winemaking may not be as developed as Kevin Kelley's at Salinia, where Wallace made his first vintage, and he isn't above admitting that one of his recently released cuvées was the result of mistakenly racking a barrel of Petite Sirah into his Mourvedre. What all of his releases have in common, though, is that they are fun to drink, and he might just be the perfect jester for the natural-wine court.

Although Donkey & Goat have acquired some vineyards, most of their fruit is purchased, making them susceptible to the whims of their growers. Hank Beckmeyer, however, is a farmer in the most traditional sense, and his farm, La Clarine, is near many of the vineyards that the Brandts work with. Rudolf Steiner, who is credited with creating biodynamics, is not the only luminary in the natural-wine world, and Beckmeyer credits Masanobu Fukuoka, the Japanese agriculturalist, with informing his farming practices.

Rather than trying to control nature, Beckmeyer describes the role of the farmer in these terms: "To promote life and to help set up an ecosystem as close to Nature as possible, whereby natural processes and systems can function." He makes a number of different cuvées, mostly in the Rhône vernacular, and his expressions of Mourvedre are true standouts, especially because of the level of freshness he manages to find in a variety that is often described as "dark" or "brooding."

5. The Entire Country of Georgia

Although recent discoveries indicate that the oldest known winery was actually in Azerbaijan, Georgia has perhaps the world's longest continuous history of winemaking (much of which would be considered "natural" now, as there is no other option when the stuff is made by individual families with small plots of grapes). Producers in this ex-Soviet Union state are not only reviving old traditions but also incorporating Western European and New World expertise.

The most natural wines are those made in the Kvevri (also Qvevri), very large amphorae often buried into the ground. The grapes, red and white, go in with their skins and all, and fermentation occurs naturally. The results can be varied, and drinkers who turn their nose up at oxidized styles of wine like sherry may not enjoy the strangely colored whites, but the beguiling wildness of the reds doesn't require any particular palate to appreciate. I might, though, prefer the cleaner expressions of local varieties like Mtsvani and Rkatsiteli, but because of the still-limited access we have to the wines, it's tough to recommend a specific wine or producer. Keep your eye out and try one if you seen it on a wine list written by someone you like or on the shelf of a store you trust.

6. Eric Texier

Eric Texier began as what is known as a négociant, meaning that he purchased his fruit from other growers. He is less dogmatic than many other winemakers who could have made this list, and he eschews some of the aspects of biodynamics, but he is unwaveringly committed to making natural wine — in the sense that he adds nothing and removes nothing from his wines.

Although he is best known for making wines from lesser-known Rhône appellations like Brézème and St. Julien et St. Alban, he actually lives in Beaujolais, a hotbed for like-minded individuals such as Marcel Lapierre and Joseph Chamonard, and he has expanded his contracts to include parcels in Burgundy and Châteauneuf-du-Pape. The wines lack the volatility of many natural wines and are approachable to any wine drinker, regardless of philosophy.

Often considered to be a king in the world of biodynamic farming, Nicolas Joly has begun to hand over the reins of the winery to his daughter Virginie. Like Nicolas, who left an investment-banking career to take over the family winery in the Loire Valley, Virginie isn't a wine lifer; she studied art and foreign languages before returning to the estate. Unlike Nicolas, who was among the biodynamic vanguard, Virginie came of age among these sometimes-radical ideas shared by other Loire vignerons, like Catherine and Pierre Breton in Bourgueil.

The Jolys' Coulée de Serrant vineyard, a monopole within the broader Savennières appellation, is often considered to be a benchmark for the Chenin Blanc variety, but, as can be expected with any natural wine, the quality has always varied. The variations, though, have at times seemed so extreme as to reflect flaws, but perhaps Virginie will bring an element of consistency to the storied estate.

8. Cedric Bouchard & Jerome Prevost

One of the problems with putting any sparkling-wine producer in the natural winemaking conversation is that such wines are inherently unnatural. Excluding Pétillant Naturel, which can be fun, if less serious, than champagne, sparkling wine requires the addition of yeast and some form of sugar to inspire the wine's secondary fermentation, capturing the resulting gas in the bottle. It's possible to do this in a relatively natural way, though, and these two winemakers are bottling transcendent fizz while adhering to some of the ideals expressed by others on this list.

Cédric Bouchard and Jerome Prevost seem to have similar ideas: both have been inspired by Anselme Selosse, of Jacques Selosse; both make champagnes from single parcels and single years, as opposed to blending, like most producers; both farm without chemical intervention; and they allow the initial fermentation to occur naturally. Bouchard works with Chardonnay and Pinot Noir under his Roses de Jeanne label, Prevost is one of few producers to bottle Pinot Meunier, the oft-forgotten variety, by itself.

They both make some of my favorite wines in the region, and as both Bouchard and Prevost are able to farm larger parcels, perhaps their bottles will become easier to acquire.

9. Andrea Calek

Perhaps no one embodies the natural winemaking spirit more than Calek, a Czech national who, according to one story about him, deserted from the army to wander around France before settling on his profession. His intentions weren't originally to make wine, and although he subsidized his nomadic lifestyle by working on various types of farms, it wasn't until he had a bottle of Beaujolais from the famed Beaujolais producer Max Breton that the proverbial switch was flipped.

He found work in France with a handful of different producers, including natural wine pioneer Gerald Oustric of Le Mazel, before saving enough to acquire some parcels in Ardèche, a region in the Rhône valley. His wines are very distinct from those from more sought-after appellations nearby, and although he is working with the same varieties (Syrah, Grenache, Vigonier), there is purity to the fruit component of his wines that reminds one that wine is an agricultural product and not something cobbled together in the cellar.

10. Elisabetta Foradori

Although there is no shortage of natural winemakers in Italy, the number of small, relatively isolated estates means there are excellent opportunities to try out new ideas. The northeastern part of Italy has long been home to producers like Stanko Radikon, who created the benchmark for orange wine. But the producer I am most excited about is Elisabetta Foradori. Not only has she embraced a natural approach at her family's winery in the Dolomites; she has also revived interest in her region's native variety Teroldego (whose popularity had been waning under pressure from international varieties).

Foradori took over the winery much earlier than anyone could have expected, after her father passed away, but her oenological innocence may have contributed to her willingness to take risks. The Granato cuvée that she produces is sleek, while having the concentration many critics might point out is missing in natural wines. Foradori has also brought her expertise to a beautiful property near the Mediterranean in Tuscany renamed Ampeleia, and the early results are stunning.

11. Sepp and Maria Muster & Ewald and Andreas Scheppe of Werlitsch

Although the Austrian wine world can seem a bit staid, there is some radical winemaking happening in Styria, in the southeast corner along the border with Slovenia. The best wines I have tasted come from two estates connected by marriage, Werlitsch and Muster.

Muster has made wine since 1727, but under Sepp and Maria, it has fully embraced biodynamic viticulture and taken on a careful winemaking approach, with as little intervention and as much patience as possible. The Zweigelt is especially good, its occasionally grizzly edges smoothed over by years in barrel before bottling. But their orange wines, bottled in clay (!!!), are stunners.

Werlitsch, with a slightly different varietal selection on the state, makes some of its most compelling cuvées from blends of Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay with less familiar varieties like Sämling and Welschriesling using a similar approach. If they can achieve some broader recognition, the synergy of these two wineries has the potential to influence the entire region.