Kings County Distillery Lets A Whiskey Grow In Brooklyn

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Welcome to What's Your Story?, our feature about innovative entrepreneurs in the food industry. What goes into the launch of a new food brand, how is the product made, who designs the packaging? All these questions, answered...

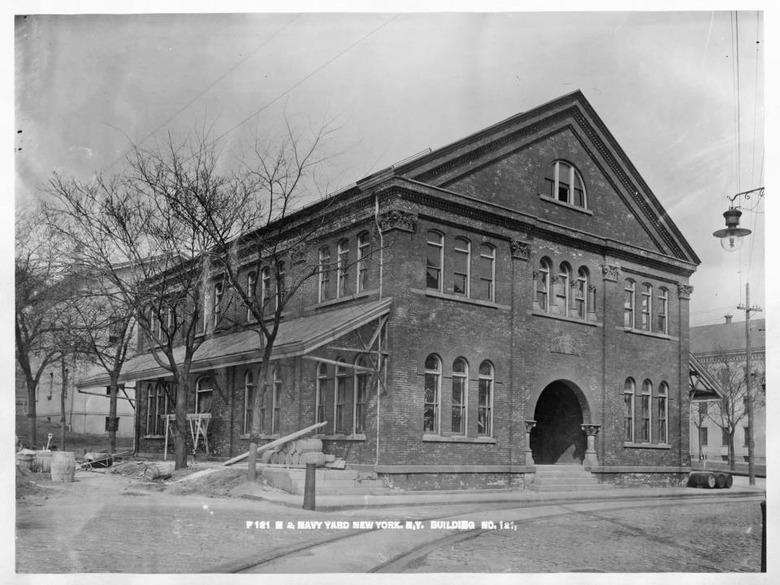

Longtime friends Colin Spoelman and David Haskell had a dream, and like so many other young mens' dreams, it involved whiskey. So the two found an aesthetically and historically perfect space in a century-old building in Brooklyn's Navy Yard, and set out to produce the first whiskey in New York City since Prohibition. That was back in 2010, and the two have grown the business, as they discuss below, and recently published a how-to so other whiskey dreamers can go for it as well: The Kings County Distillery Guide To Urban Moonshining. Spoelman, a Kentucky native who started distilling as a way to combat his homesickness, reveals the Kings County Distillery story here.

How did you go about moving into the distillery and starting up the business?

I was making moonshine in my apartment long before we had any plans to start a business. It was just something fun and unusual to kill time on weekends. Very quickly we realized people were interested in the product. It's illegal to make your own spirits, so in an effort to not get too deeply in trouble we couldn't get out of, we started the business legally in a small, one-room commercial space, then after a couple of years we expanded to the building where we are today: the Paymaster building in the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

It's not that we restarted an existing business; we just happen to be the oldest whiskey distillery in the city (at only about three years old). Still, there were a lot of distilleries in the 1800s in the neighborhood adjacent to the distillery and there were historic confrontations between troops stationed at the Yard and the illegal "moonshiners" of Brooklyn in the 1860s and 1870s, so the site does have significance.

What were you and David doing before launching the company, career-wise?

David and I both still have our day jobs, though I'm part-time. He is the [deputy] editor of New York magazine and I work in architecture. A lot of people at the distillery do something else on the side. Our whiskey is aged an average of 18 months right now, but as we grow, that will grow too. It means we depend on what we made a year and half ago to sustain us, so we are making a lot more than we have available to sell. We're keeping our day jobs until the whiskey catches up. Whiskey is a hard spirit that way.

Why distilling?

Whiskey is like alchemy. There's a magical aspect to it, which has been romanticized for centuries: you turn this very unpalatable grain slop into something that looks a lot like liquid gold. It takes careful refinement, then you have to sit on it for as long as you can stand until it hits a sweet spot. It's a way to measure time, in liquid. Also, I like to drink whiskey, so it's not too much of a stretch.

Did you have previous experience in the industry?

None whatsoever. The closest I came was bartending on Thursday nights after college, but I was pretty quickly fired, I assume for incompetence. I think we're very much outsiders to the world of distilled spirits, which is fine by me. That may have to change as we grow, but a lot of our business is predicated on ignoring the conventional wisdom about what a whiskey company has to be (for one, being in NYC instead of rural Kentucky), so I think it's an advantage. Because I learned to distill in my apartment, I could determine firsthand what I felt were the important variables for making good whiskey and I could learn with authority, at least for my own palate, what I thought made a difference.

Tell us about the distilling process.

The moonshine was what we'd been refining for a couple years on the back porch of the apartment. It's a double pot-distilled spirit, which is more unusual for an American whiskey than it sounds, and made with organic local corn and malted barley from the UK. When starting the business, we knew that the moonshine would stand up to scrutiny since unaged whiskey at the time was a very narrow and overlooked category. Bourbon is an aged version of the moonshine, and because it's well-distilled, it stands up to more established whiskeys.

What is your best-selling product?

The bourbon is most popular, but it's also the most familiar. We also make a chocolate whiskey that we'll be rolling out to stores in 2014, and I expect that to be quite popular, since it's just completely different than anything else out there.

What has been your proudest moment?

In the movie Drinking Buddies, the Ron Livingston character is dating a young woman who works at a craft brewery. He's not that interested in beer, so he pours himself a whiskey, and it's a bottle of Kings County. That was pretty cool.

What advice would you give a food/drink-centric small business?

Stick to your values as you grow, and it will stay fun. The fear with any small business, I think, is that it becomes drudgery, even something like making whiskey. But the hard work can add up, and as you grow you have to make sure to come up with creative ways to keep it fun and meaningful. For us, writing the book was a way to articulate what we think makes good whiskey and to state some of the values that we believe in as a business (and as people). Right now we do our own distribution in New York and have distributors in Connecticut and New Jersey. We're also a very tiny bit in California, Sweden and Japan.

What are some of your long term goals with the company?

When we started the distillery, there were maybe 100 craft distilleries in the country. One industry watcher says that could climb to 1,000 in five years. I think we just want to make a good product and remain relevant among our peers, even as the market gets more crowded. We have a barrel that's designed to age 25 years, so I'd love for the business to last long enough to drink that bourbon.

What about the branding? Do you do it yourself?

I had a typewriter that I was using to type up labels back when we were making whiskey in the apartment, so the final labels aren't much different than they were way back then. Just wanted to keep it simple and put the focus on what's in the bottle, not so much on what's on the bottle.

[Read about more food and drink entrepreneurs in What's Your Story?]