The Very Disturbing Origins Of Corn Flakes

The name "Kellogg" sparks images of grinning tigers, overstimulating supermarket aisles, and easy breakfasts. But in the not-too-distant past, the name stood for something very different. John Harvey and Will, the brothers Kellogg, began the 20th century running a health spa in Battle Creek, Michigan. John Harvey was the visionary behind the operation, while Will kept the books in order. By all accounts, they were extremely successful.

So when John Harvey invented the original "health food" as an antidote to the hulking breakfasts of the time (often meat and potatoes fried in the previous night's drippings, or for the elite, breakfast buffets and dishes like classic eggs Benedict), it was bound to be a success. After all, America was changing. The industrial age had arrived, and most people no longer needed huge breakfasts to fuel them for days of manual labor; now, they wanted a quick fix before heading to the factory or office. And so, after much trial and error, Kellogg's Corn Flakes were born.

But John Harvey was a eugenicist. He was a proponent of "race betterment," a racist theory that influenced forced sterilizations across America through laws targeting African-Americans (some of which are still in force today). He was a religious fundamentalist, decrying masturbation, sex, alcohol, and meat — and though he branded this philosophy as "clean living," the ultimate goal was to rid people of "impurity." His cereals, John Harvey believed, were essential in achieving this — bestowing his creation with a surprisingly disturbing origin.

The invention of Kellogg's Corn Flakes

John Harvey's first attempt at cereal, a tooth-breaking mix of ground oat biscuits eventually known as "granola," was a minor success. Patients at Battle Creek enjoyed it and asked to take it home — the first inkling that there was a business to be made in packaging these new breakfast cereals. So what were Corn Flakes originally invented for? John Harvey realized that his granola was impractical for many of his patients, who suffered from fragile teeth or diseased gums, to chew. He needed to create a cereal that, while toasted, could be given to patients without any additional liquid (stimulating saliva production was another of his goals) — and eventually, he found it: by complete accident.

So the story goes, in 1898, a batch of cereal dough (made of wheat, not corn) was left unattended, causing it to ferment. When rolled out and baked, it formed perfectly crispy, crunchy flakes. Over the next few years, John Harvey's brother, Will, tweaked the recipe, eventually landing on the popular form we know today. Will, who had considerably more business acumen than his brother, was largely responsible for turning Kellogg's Corn Flakes into a phenomenon. However, the way he did it — by breaking away from John Harvey's doctrinal ways (and their company) and altering the recipe (by adding sugar) to make it more palatable — led to a years-long lawsuit and a feud that lasted the rest of their lives. Kellogg's Corn Flakes' origins were not only disturbing but tragic, too.

Corn Flakes' success destroyed Kellogg family ties

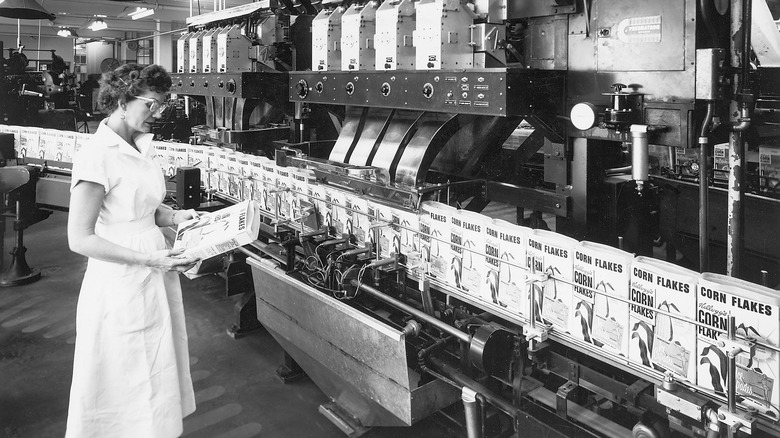

Kellogg's Corn Flakes' success was immediate, but John Harvey's commitment to bland and healthy foods (far from the delicious, crunchy, chocolatey granola, protein-rich varieties, and cereals we're now familiar with) wasn't a recipe for sustained success. Will, however, saw the opportunity they had. John Harvey didn't care about sales; he cared only about promoting his vision of health for Americans. So Will struck out on his own, began selling his sweeter-tasting, more enjoyable version of their product, and soon turned it into an icon.

As the Kellogg empire grew, the relationship between the brothers deteriorated. A years-long legal battle ensued over which Kellogg was the "true" Kellogg. In the end, Will won. Though John Harvey had been the initial brains behind the operation, his tunnel vision cost him. He was forced to pay huge sums in legal fees and was prevented from ever selling a cereal under his family name again, save for a small note on the corner of the packaging. The brothers barely spoke for the rest of their lives. But Kellogg's Corn Flakes also (in a way) saved John Harvey's name. Today, we think of them as America's favorite cereal, or even as a great coating alternative to add crunch to fried chicken, but their disturbing origins remain largely unknown. By ensuring that John Harvey couldn't use his own name in life, Will unknowingly — whether for better or worse — preserved his brother's legacy and his invention.